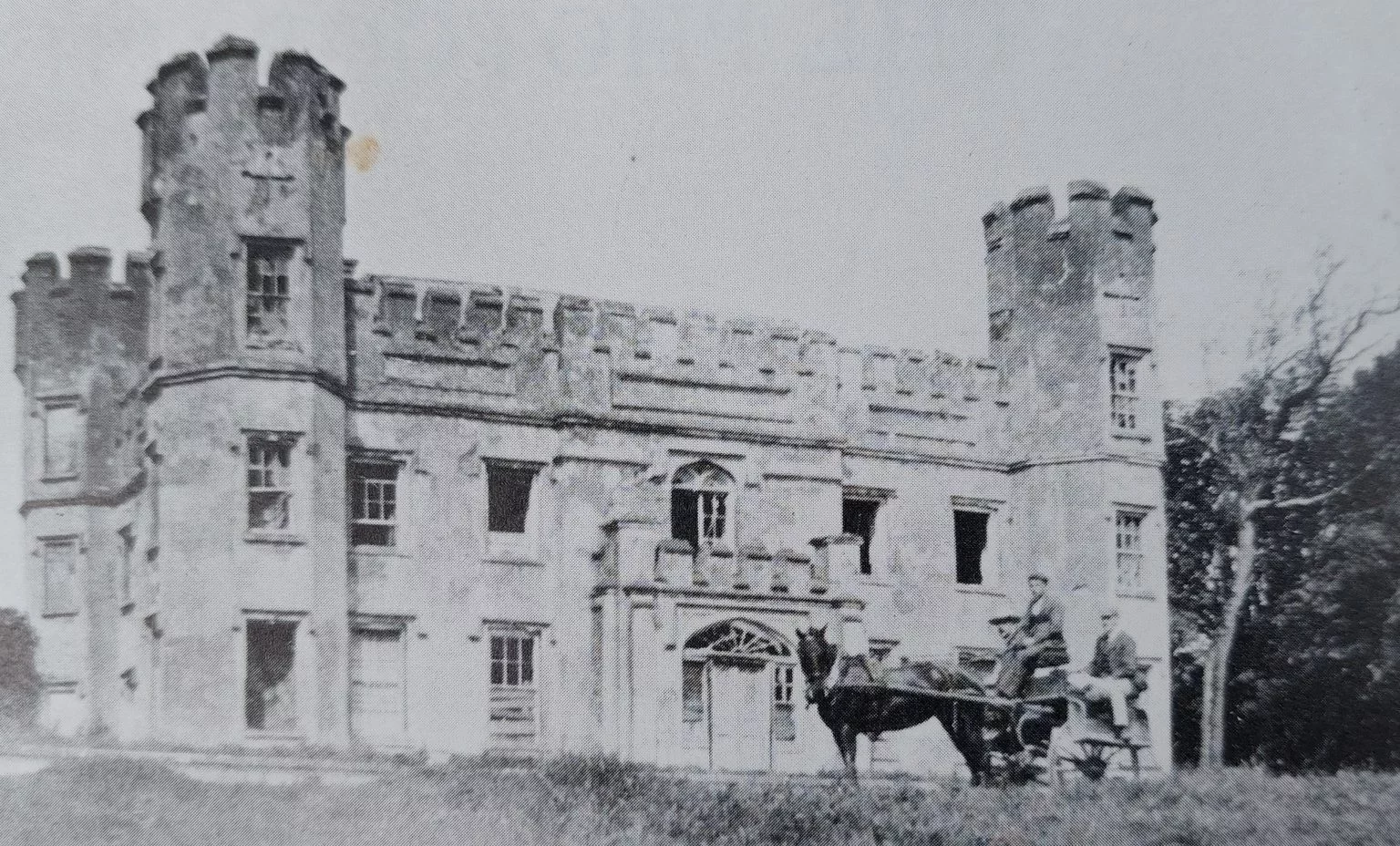

Birchfield House — The O’Briens’ Country Seat

The House and Its Lineage

Birchfield House was built in the late 18th century, likely on lands long associated with the O’Brien dynasty — the same family that left their mark with O’Brien’s Tower at the Cliffs of Moher and the O’Brien Column near Liscannor. Birchfield was never as flamboyant as those follies; it was a family seat, a home designed to project refinement and authority in the Georgian style.

Its symmetrical frontage, sash windows, and fanlit doorway marked it out as a house of status. Inside, it would once have had polished timber floors, high-ceilinged drawing rooms, and fireplaces lined with Liscannor Stone. The surrounding demesne included walled gardens, pasture fields, and avenues planted with birch trees that may have given the estate its name.

The O’Brien Residents

The Birchfield O’Briens were a junior branch of the wider Thomond O’Briens. While the main line produced MPs and lords, Birchfield’s residents managed a more modest estate — but still with enough wealth to act as landlords to the surrounding tenant families.

One of the better-known figures associated with Birchfield was Cornelius O’Brien (1782–1857), the same MP and landlord who built O’Brien’s Tower at the Cliffs. Though he is more strongly linked with his Cliffs and Liscannor projects, oral tradition holds that Cornelius and other family members frequented Birchfield, and that tenants on its lands supplied both labour and rents that underpinned his building works.

Later, as the 19th century wore on and the O’Briens’ fortunes shifted, Birchfield saw changes in ownership and tenancy. Like many Irish “Big Houses,” it passed through phases of grandeur, decline, and adaptation, reflecting the turbulence of Clare’s landlord system.

Gossip, Grandeur, and Hardship

Local lore remembers the Birchfield O’Briens in mixed tones:

Patronage and Pride: They brought employment through estate works and follies, and were said to have encouraged tourism to the Cliffs, which in turn benefited local trade.

Pomp and Vanity: Others accused them of vanity projects — raising towers and monuments while tenants lived in poverty.

Famine Shadows: During the Great Famine (1845–1852), houses like Birchfield became symbols of contrast — genteel dinners in high-ceilinged parlours while tenants outside faced starvation. Some accounts say Cornelius did provide relief works and supported soup kitchens, but memories are divided, blending gratitude with resentment.

Survival into Modern Times

Unlike many country houses in Ireland that were torched or abandoned during the revolutionary period, Birchfield survived — though not unchanged. Parts of the estate lands were broken up under the Land Acts of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when tenant farmers gained the right to purchase holdings. By then, the “Big House” era was in decline, and Birchfield became quieter, less a symbol of dominance than a relic of a fading world.

Today, the house still stands, its stone walls softened by ivy and weather. To walk its grounds is to sense echoes of both refinement and contradiction: a home that embodied elegance while sitting at the heart of a system that bound tenants to landlords, privilege to hardship.

Why it Matters

Birchfield House is more than an old residence. It represents the “Big House” story in Clare: the rise of Georgian estates, the power of families like the O’Briens, the tensions of famine and landlordism, and the endurance of architecture that outlived its social order.

For visitors, it offers a lens into another side of Liscannor’s past — not the wild cliffs or quarries, but the domestic world of gentry houses, where politics, pride, and everyday life intertwined in stone.

Other Heritage sites

Cliffs of Moher

Discover a place where deep time, nature, and myth converge. The Cliffs of Moher began their story 320 million years ago, a geological history visible in their fossil-rich layers of rock. Today, these ancient walls are alive as a protected haven for tens of thousands of seabirds, including puffins and falcons. This dramatic setting has inspired centuries of folklore, from the legend of the witch Mal at Hag’s Head to tales of lost Armada treasure, making the cliffs a landmark carved by both the ocean and the human imagination.

Seamount House — A Landmark of the Atlantic Gentry

Perched above Liscannor Bay, Seamount House is a striking early-19th-century Georgian/Regency residence built for the O’Brien family. With its grand sash windows and sweeping sea views, it embodied the confidence of Ireland’s “Big House” era — a world of elegance and privilege sustained by the labour of local tenants. Today, though softened by ivy and time, it remains a powerful reminder of both the grandeur and the contradictions of landlord life in Clare.

Ready to Explore Liscannor?

Questions? Need directions or recommendations? We’re here to help you make the most of your time in Liscannor.